Did the Olympic Sink in 1912?

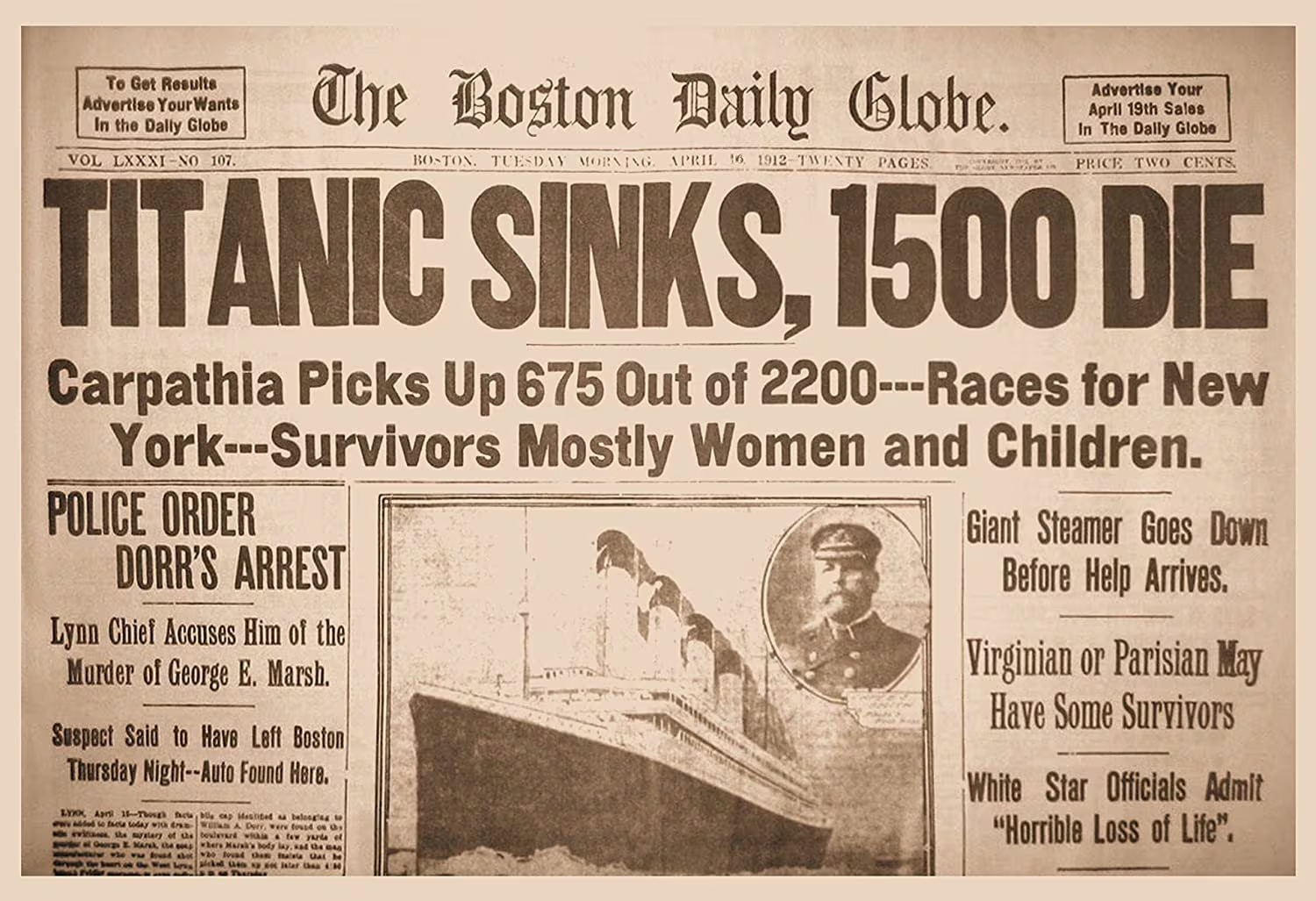

For over a century, the sinking of the RMS Titanic has been remembered as one of the greatest maritime tragedies in modern history. On April 14–15, 1912, the so-called “unsinkable” liner struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic, leading to the deaths of more than 1,500 passengers and crew. But alongside the well-documented story sits a controversial alternative claim: that it wasn’t the Titanic at all that sank that night, but her nearly identical sister ship, the RMS Olympic, disguised in a secret swap.

Known as the “Titanic switch theory,” this claim has been circulating for decades, fueling books, documentaries, and late-night debates. But what exactly does the theory say, and how does it stand up against historical records?

Where the Switch Theory Comes From

The origin of the switch idea lies in the uncanny similarity between the White Star Line’s Olympic-class ships. The RMS Olympic (launched 1910) and the RMS Titanic (launched 1911) were sister ships, built side by side at Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast. Outwardly, they were nearly identical — so much so that even experienced crew members sometimes confused early photos of the two.

Supporters of the switch theory point to one key moment: in September 1911, the Olympic collided with the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke. The crash caused significant damage to the Olympic’s hull and keel, leading to costly repairs and lost revenue for White Star Line. From this point forward, some theorists argue, the groundwork for a cover-up was laid.

Key Claims Made by Believers

Over the years, proponents of the switch have highlighted several pieces of supposed evidence.

- Insurance Motive

The Olympic, damaged in the 1911 collision, was allegedly more expensive to repair than insure. By swapping the ships and sending the damaged vessel to sea as the “Titanic,” White Star could claim insurance money on a vessel they knew was doomed. - Photographic Differences

Believers point to small but noticeable design details between photos of the Olympic and Titanic: variations in the number of portholes, the arrangement of windows, and differences in deck fittings. They argue that the ship that sank matched Olympic’s features more closely than Titanic’s. - Crew Testimony and Suspicion

Some accounts suggest that crew members were uneasy about the voyage, with rumors that seasoned sailors refused to serve on Titanic’s maiden crossing. The theory holds that these sailors “knew” the ship was really Olympic and feared disaster. - Survivor Accounts

A handful of survivor testimonies mention odd discrepancies — details about the layout of corridors or fittings that didn’t quite match Titanic’s known design.

What Historians and Experts Say

Mainstream maritime historians, however, reject the switch theory as implausible. Several lines of evidence support their view:

- Shipyard and Registry Records

Harland & Wolff kept meticulous construction logs, marking every stage of Titanic’s build. These records, including hull numbers (401 for Titanic, 400 for Olympic), are still preserved. When Titanic sank, parts recovered from the wreck bore markings consistent with hull 401. - Repair and Refitting Documentation

Many of the supposed “photographic differences” can be explained by retrofits and changes carried out during construction. Ships often underwent modifications before and after launch, making side-by-side comparisons misleading. - Insurance Reality

While insurance was a factor in all shipping operations, experts point out that the alleged scheme would have been financially reckless. A deliberate sinking would have risked the company’s survival and exposed White Star to massive liability if uncovered. - Survivor Consistency

The majority of survivor accounts align with Titanic’s documented layout and fittings. Inconsistencies are usually attributed to the trauma of the disaster and the passage of time.

The Role of Photographs

Photographs form one of the most compelling visual hooks for the switch theory. Advocates highlight details such as:

- Titanic having 14 portholes on a particular deck versus Olympic’s 16.

- Differences in deck-level windows and ventilation covers.

However, photographic historians caution that images taken from different angles, lighting conditions, or stages of fitting out can create misleading comparisons. What looks like a discrepancy may simply be the result of perspective or a temporary alteration.

Timeline of the Olympic and Titanic

- October 1910: Olympic launched, begins service in 1911.

- September 1911: Olympic collides with HMS Hawke; repaired at Harland & Wolff.

- May 1911–April 1912: Titanic completed, launched, and outfitted.

- April 10, 1912: Titanic departs Southampton on her maiden voyage.

- April 14–15, 1912: Titanic strikes iceberg, sinks.

This timeline demonstrates the overlapping lives of the two ships but also shows how closely their construction and refits were documented.

Why the Theory Persists

So why does the switch theory endure despite the evidence against it? There are several reasons:

- Similarity of the Ships: With two nearly identical liners, confusion is inevitable.

- Mistrust of Institutions: The Titanic disaster itself highlighted failures by White Star and the British Board of Trade, feeding skepticism about official accounts.

- Human Fascination with Conspiracies: From the moon landing to Roswell, alternative explanations for famous events capture the imagination. The Titanic, as a cultural touchstone, is no exception.

Conclusion: Fact, Fiction, or Something In Between?

The Titanic switch theory remains a captivating “what if” story in maritime lore. It combines real historical details — the Olympic’s collision, White Star’s financial pressures, and the two ships’ striking similarities — with speculation about motive and evidence.

While the vast majority of historians and technical experts dismiss the claim, its persistence shows how alternative narratives thrive when gaps or inconsistencies appear in official stories. For those exploring the edges of history, the theory serves less as a proven fact than as a case study in how myths, suspicions, and conspiracies take root.

Whether you see it as a fascinating puzzle, a cautionary tale about skepticism, or just a curious sidebar in Titanic history, the switch theory continues to remind us how easily history can become legend.

8sbet, eh? Never heard of it, but always up for trying something new. Hope 8sbet got some good odds! Wish me luck.